Our youngest son, 16 year old Emmett, does not enjoy school. Socialization and sports make it tolerable, and perhaps enjoyable, at times. Emmett has always done reasonably well in school, so his apathy toward school can’t even be blamed on a struggle with learning. He doesn’t seem to value the educational opportunities that exist; he often asks, “What’s the point?” or “When will I ever use this outside of school?” This is an incredibly tough pill to swallow for me, an educator, who lives and breathes the value of an education. When I think about Emmett’s attitude toward school, I am wracked with guilt (Where did I go wrong?), frustration (Why can’t he take responsibility for his own learning?), and wonder (How often has Emmett been given the opportunity to be a leader of his own learning?).

Emmett Reed Kruse, Homecoming, Oct. 2, 2021

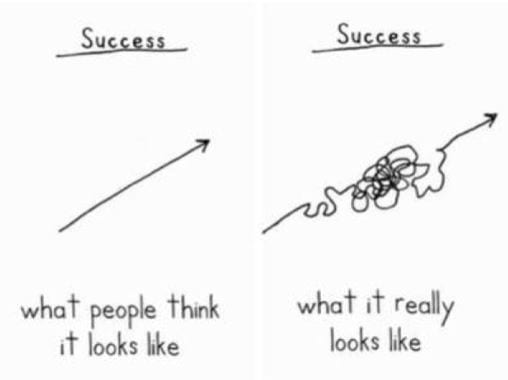

Beginning with the End in Mind In February and March, I wrote about the importance of teachers beginning with the end in mind, meaning that as they plan instructional sequences, it would behoove them to use the principles of Understanding by Design, a “backwards design” format. When teachers become crystal clear about the learning goals for an instructional sequence, they can lead their students to become crystal clear about the learning goals. In addition to gaining clarity around where we are heading, we must embrace the idea that the journey to get to that end goal will likely be messy. Demetri Martin shares the following image about success, while George Couros challenges us to think of that same image as it applies to learning:

Demitri Martin’s “Success” image

George Couros version

Learning Targets and Standards In addition to being crystal clear about the end goal (derived from a standard) in a learning progression, teacher teams must have established learning targets. I explained the origin of these targets in an April post: “These targets are derived from the standard and are written with concrete language that students are able to understand; they begin with the stem, “I can…,” allowing students to take ownership of their own learning.” There are a multitude of ways that students can take ownership of their learning beyond knowing what the learning targets are. Teachers can post learning targets for each lesson, leading students to verbalize the learning targets at the beginning of a lesson, check in on their progress toward meeting the targets throughout the lesson, and check on their progress toward meeting the targets at the end of the lesson.

Tracking Progress As students progress toward meeting a standard through learning targets, they can check in on their progress during the lesson, as stated above. In addition, they can articulate their progress (I’ll talk more about this in a bit), and they can chart their progress. I shared the following graphs in that same April post about learning targets. Robert J. Marzano shared these graphs in a December 2009 ascd article, where he states, “On average, the practice of having students track their own progress was associated with a 32 percentile point gain in their achievement.

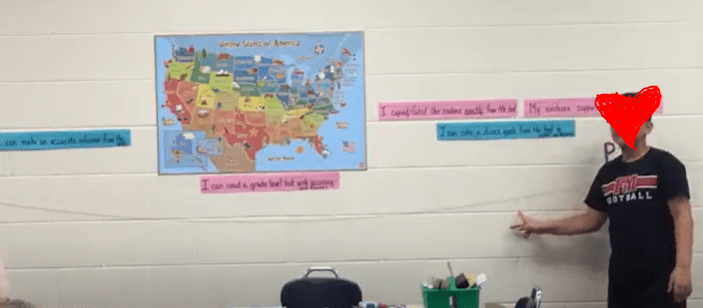

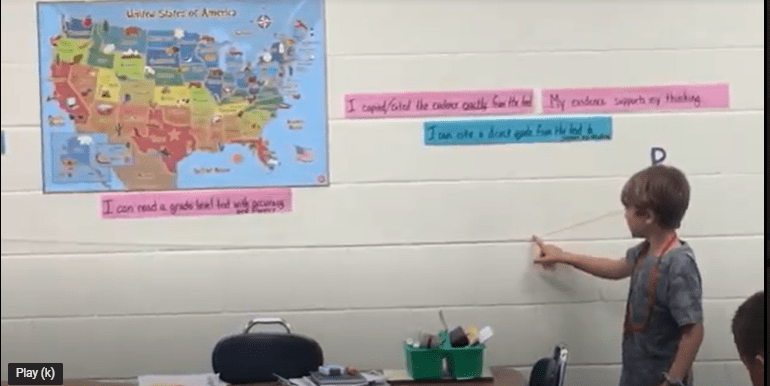

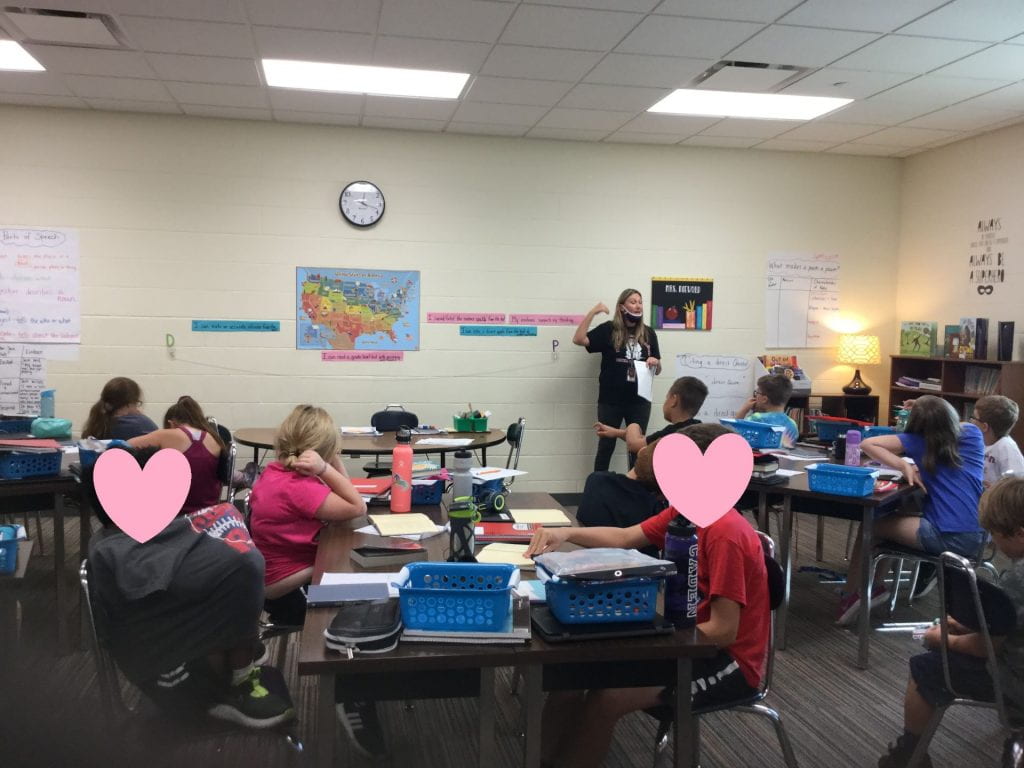

Articulating Proficiency This past week I was blown away when I watched students in Amy Diewold’s fourth grade class describe their own level of proficiency toward meeting the ELA standard, RL.4.1: “Refer to details and examples in a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text.” From the beginning of the year, Ms. Diewold has used a rope analogy to assist students in understand our FMCSD K-8 proficiency levels, which currently consist of three descriptors: “No Evidence,” “Developing,” or “Proficient.” Each teacher team has developed proficiency scales so that the criteria for achieving proficiency are clearly outlined. The rope analogy helps students visualize the breadth of “Developing”: there is a huge range in what constitutes “Developing” toward proficiency! In the picture below, note the “D,” on the left which, along with the entire rope, represents “Developing.” On the right hand side of the rope, the “P” represents “Proficiency.”

Ms. Diewold explaining the “Proficiency Rope”

Even more exciting than the image Ms. Diewold has created for her students, is the next step: after administering common formative assessments, she asks volunteers to come up to the proficiency rope and explain what their proficiency level is (No Evidence, Developing, or Proficient) on that standard, according to an item from that most recent common formative assessment. This is powerful stuff, folks! When students can articulate their progress in this manner, they have clarity about the intended learning, and are most definitely becoming leaders of their own learning!